Holocaust Memorial Day - Fragility of Freedom

26 January 2024

Holocaust Memorial Day (HMD) takes place each year on 27 January in remembrance of those murdered during genocides around the world.

Holocaust Memorial Day Trust (HMDT) encourages remembrance in a world scarred by genocide.

We promote and support Holocaust Memorial Day (HMD) - the international day on 27 January to remember the six million Jews murdered during the Holocaust, alongside the millions of other people killed under Nazi Persecution and in genocides that followed in Cambodia, Rwanda, Bosnia and Darfur.

This year, join the nation to watch curated moments from the Holocaust Memorial Day (HMD) 2024 UK Ceremony before taking part in the Light the Darkness national moment

The UK Ceremony for Holocaust Memorial Day (HMD) will be streamed live at 8pm on 27 January 2024.

Households across the UK are being asked to join the ceremony and to:

- remember those who were murdered for who they were

- stand against prejudice and hatred today

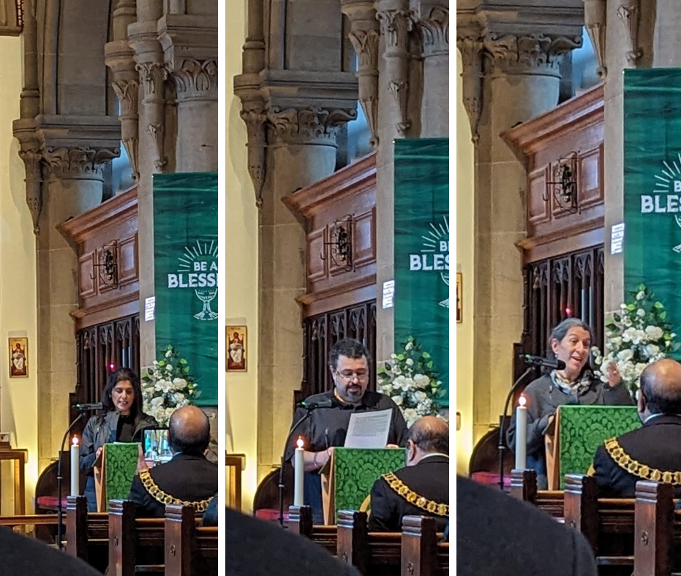

Holocaust Memorial Day Service

Holocaust Memorial Day Service took place at St George, The Martyr Church in Preston, at 11am on Friday 26 January 2014.

The guest speaker was Lady Milena Grenfell-Baines, who as a child was brought to the UK in 1939 along with many others by Sir Nicholas Winton.

The Testimonies from the service are available to view below.

The testimony of Martin Stern, a Holocaust Survivor

Martin Stern was born in 1938 in the Netherlands. His parents were German, but fled to the Netherlands in part because Nazi laws in Germany forbade his non-Jewish mother from marrying his Jewish father.

When Martin was two years old, the Nazis invaded the Netherlands. His father could not continue his work as an architect and had to go into hiding. Martin's mother died after giving birth to his sister and the non-Jewish couple who looked after him whilst his sister was born continued to do so for two years, pretending he was their son. One day, two men came into his school and asked if Martin Stern was there. His teacher understood that he was in danger and lied, saying that he was not in school that day. Unfortunately, Martin was too young to understand, so he identified himself and went with them. Martin later discovered that the man who had been looking after him for two years was sent to a concentration camp as punishment, where he was murdered.

Two young men in civilian clothes unexpectedly walked in and one of them asked 'Is Martin Stern here?' And the teacher immediately shot back 'No, he hasn't come in today.' And there I was. I didn't understand what was going on. I put my hand up, and I said, 'But I am here.' And as these two young men were leading me out of the room, I looked back, and I'll never forget the ashen face of the young teacher.

Martin and his sister Erica were both sent to Westerbork transit camp. Martin was five and Erica was one. There, Martin watched people being forced into cattle trucks and sent away, until it was his turn. He remembers a train so crowded they had to stand for their journey, which lasted about two days and nights. They arrived in Theresienstadt, a concentration camp north of Prague.

The conditions were appalling, with very little food and terrible hygiene; there was an outbreak of typhus spread by the lice. A Dutch woman, Mrs Cathariena De Jong, looked after Martin and his sister, even stealing food for them. She stood ready to board the train which would have taken them with the other children to their deaths, but their names were not called. On 8 May 1945, the Soviet army entered and liberated the camp, although it was some time before the prisoners could leave.

After returning home to the Netherlands, Martin was sent from family to family, before moving to stay with relatives in the UK. He learnt English and did well at school, going on to become a British citizen aged 16 before studying Medicine at Oxford University. Martin worked as a hospital doctor living with his family in Leicester for many years.

Today, he dedicates his time to sharing his story with groups across the UK, also teaching about other genocides and what it is about the human mind which makes such horrors possible. He often thinks about the other young children who were his friends in the camps, who did not survive.

Dr Martin Stern will be the guest of honour at the Leeds Holocaust Memorial Day service this weekend.

The testimony of Hasan Hasanović

Hasan Hasanović was 19 when the town of Srebrenica fell to Bosnian Serb forces in July 1995. He endured a 100-kilometre march through hostile terrain to escape the massacre of around 8,000 Muslim men and boys that took place there.

Hasan Hasanović was born on 7 December 1975 in Bajina Bašta, Serbia. He lived in the village of Sulice, Bosnia, 35 kilometres south of Srebrenica, until the family moved to Bratunac in 1991. When the Bosnian War started in March 1992, towns in the east of the country came under attack from Bosnian Serb forces. By May, Hasan's family had been forced to move to the Muslim-held enclave around the town of Srebrenica which was to become the first of the United Nations' so-called 'Safe Areas' in April 1993.

By this date, the Srebrenica enclave was under siege, cut off from friendly territory to the west and packed with about 60,000 people, mainly Muslim refugees like Hasan from the surrounding area. There was no electricity, very little food, and people were being killed every day by Serb artillery fire.

The Srebrenica enclave fell to Bosnian Serb forces on 11 July 1995. Uninhibited by the presence of Dutch UN peacekeepers, the Serbs commenced the slaughter of around 8,000 Bosnian Muslim men and boys, the worst massacre in Europe since the Holocaust. Hasan remembers listening to reports from the frontline, expecting the international community to step in and protect them, then being shocked to hear that the UN troops were retreating without offering resistance.

Hasan, along with his father Aziz and twin brother Husein, decided to flee. They joined 'the column': between 10,000 and 15,000 Muslim men, mostly unarmed civilians, setting out on a gruelling 100-kilometre march towards the Muslim-held town of Tuzla. The terrain was mountainous and littered with minefields, and many Serb soldiers lay between Hasan and safety:

'It wasn't going to be an easy journey, but we had no other option. We wanted to live.'

The Hasanović men stuck to the middle of the column as it assembled, for safety. But the Serb forces could see the gathering men from their positions on the hills and opened fire.

'They didn't care that we were unarmed. Their primary concern was that we were Muslim, and they wanted us dead.'

Some men were killed; others scattered in panic. In the confusion Hasan became separated from his father and brother. He wanted to stop and look for them, but he knew that if he did, he would likely be killed.

'I could think of nothing but pushing forward. Forward was freedom; forward was survival; forward was everything... I told myself if I wanted to live, I would have to run and not look back.'

He would never see his father or brother again. Hasan fled into the woods with many other men, but by the afternoon of 12 July they had lost contact with the front of the column. They were attacked again, bullets ricocheting off the trees all around. The Serbs were very close.

'I was terribly scared, lost all my strength and threw off the backpack, even the jacket I was wearing. I could not move. But I came across some guys I knew who gave me sugar and water, and all of a sudden it gave me the strength to go on.'

During the night of 12 July Hasan's group caught up with the front of the column, and the exhausted men took a break to rest.

'I couldn't look at anyone. The instinct to survive is a powerful one, but nothing spells death like the face of a helpless man. So, we just looked away from each other.'

The next day the men of the column gathered on Kamenica Hill, about 60 kilometres from Tuzla.

The Serbs attacked again, killing thousands that day alone. Hasan hid in the forest once more, whilst Serbs using loudspeakers and stolen UN uniforms attempted to trick them out with promises of food and safety. Those who did give themselves up were made to call their relatives out from hiding. They were then taken away to be murdered and buried in mass graves.

On 14 July those who had escaped the ambush continued their trek through the forest towards Tuzla. Hasan was so tired he slept on his feet as he walked. As they came to a road, someone shouted that a Serb tank was coming.

The men fell to the ground and lay still. Hasan was lucky; the Serbs passed by without noticing them. Later they came to a river and struggled across.

'We weren't soldiers who had prepared for this kind of journey' says Hasan. 'We were just ordinary men.' When he reached the other side, he removed his boots.

Days of walking had turned his feet into a blistered mass of agonizing pain. He wanted to lie down and sleep, but another man told him, 'If you sleep now, you'll sleep forever'.

The men reached the Baljkovica Valley, agonisingly close to friendly territory. Here they waited nervously while the few armed Muslims exchanged fire with Serb soldiers. Hasan hid in a stream for two hours, weak and delirious from lack of food and water. Finally, they were told to dash across the valley and made it to the free territory of Zvornik. They were welcomed with food and water, and buses lined up to take them to a ruined school, where they slept. The next morning, having walked for five days and six nights, Hasan was driven to Tuzla.

'I couldn't believe I had survived.'

Hasan was one of only 3,500 who survived the march. He remembers arriving at the bus stop in Tuzla and being met by women deported from Srebrenica, desperate for news of their loved ones:

'I was at a loss. I didn't know what to say. I didn't want to upset them, and the truth was that they were probably all dead.'

Weeks later Hasan was reunited with his mother and younger brother at a refugee camp at Tuzla airport. He kept hoping that his father and twin brother might still be alive.

'That hope lasted until the first discovery of the mass graves.'

Hasan's father and brother were found in mass graves excavated by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) after the war. Hasan buried his father at the Srebrenica Memorial Centre in Potočari in 2003, and his brother in 2005. He still does not know how and where they were killed. After the war, Hasan worked as an interpreter for the US army. He then gained a degree in Criminal Sciences and returned to live in Srebrenica in 2009. Moving back was a painful experience:

'It is hard to live in a town full of emotion. Every street, every building and every house reminds you of what you have survived.'

Hasan is now married and has a young daughter. He works as a Curator at the Memorial Centre, where he shares his story with visitors from all over the world on a daily basis. He sees this as both his duty to those who were murdered and a cathartic experience for himself.

The testimony of Mushimire, a survivor of the Rwandan genocide

This is the testimony of Mushimire, a survivor of the Rwandan genocide I was the youngest in my family of nine children, five of whom were killed during the genocide and massacres of 1994.

I was three months pregnant when my husband died. We had been living together for only four months. On April 6, 1994, before we had even learnt of Habyarimana's death, a militia took my husband claiming he knew where the rebel who had killed him was hiding. After three days of waiting for him to return, I gave up on him. On the third day I was attacked and taken captive by a big group of militia. At the village authority offices, I found many other women with whom I was then imprisoned for a month. During this time the militia would come to rape us.

I can't recall how many men raped me altogether. After raping us they returned us to the cells. But one time after another, the rape continued. They were against pregnant women. They threatened to cut open my womb, and they did whatever they could to try ensuring that I would miscarry.

After a month, and on the verge of dying, I managed to escape. I hid by a pond, living on its banks for the next month; feeding on grass and water.

At the end of May 1994, the militia discovered my hiding place. A man named John, one of the militias that had taken my husband, pretended to have mercy on me and took me back to his home. But all he wanted was to rape me.

I was weak but it seemed not to bother him at all. Even when I bled, thinking that I was going to miscarry, he continued raping me. Even when I told him that I was in pain, he continued raping me. He did eventually give me food and water to bathe in, but by then I could neither eat nor bathe myself. He left me in his house, saying that I must leave by the time he returns. I crawled and hid in a bush near his house. I was so exhausted; I must have passed out. When I awoke, I was rotting and covered in maggots. John did not return. I later learnt that he had fled on hearing that Kigali had fallen. I was rescued and taken to a school.

Many injured people were being treated there. I found that my sister had survived, and by a miracle of God, my pregnancy survived the ordeal.

I had a son, which cheered me up. I also heard that my mother had survived, and I returned to live with her. I suffered complications and constant infection following the genocide, which is why I took an HIV test.

The result was positive. I was not surprised given the ordeal I had lived through. I began to hate myself, and everything around me, including my own son. I am currently taking very expensive medicine, which helps ease the pain and increases my immunity to most sicknesses. Taking the medicine requires one to eat well. But sometimes I can't afford food. I must live with the pain of having only enjoyed four months of marriage. My Mom always tells me to remarry, but that is because I have never plucked up the courage to tell her about my sickness. Because of my ordeal, I have come to hate all men irrespective of their race or looks. But I am glad that my son did not contract the HIV virus.